Present: works from the immersive exhibition

In the history of the Mediterranean, the roles and place of women have evolved with wars, conquests, alliances and trade relations. The objects, works of art and relics that have come down to us tell us a rich and complex story, sometimes far from our preconceived ideas.

Find on this page the works of the immersive exhibition "Présentes".

Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa

This portrait by Leonardo da Vinci is one of the most famous female portraits in the world. The identity of the sitter has been the subject of many interpretations. Today, it is accepted that she is Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a Florentine cloth merchant. The work's fame stems from its enigmatic smile and the artist's technical mastery, particularly in the rendering of detail and the use of sfumato. This portrait embodies the ideal of beauty and humanism of the Italian Renaissance.

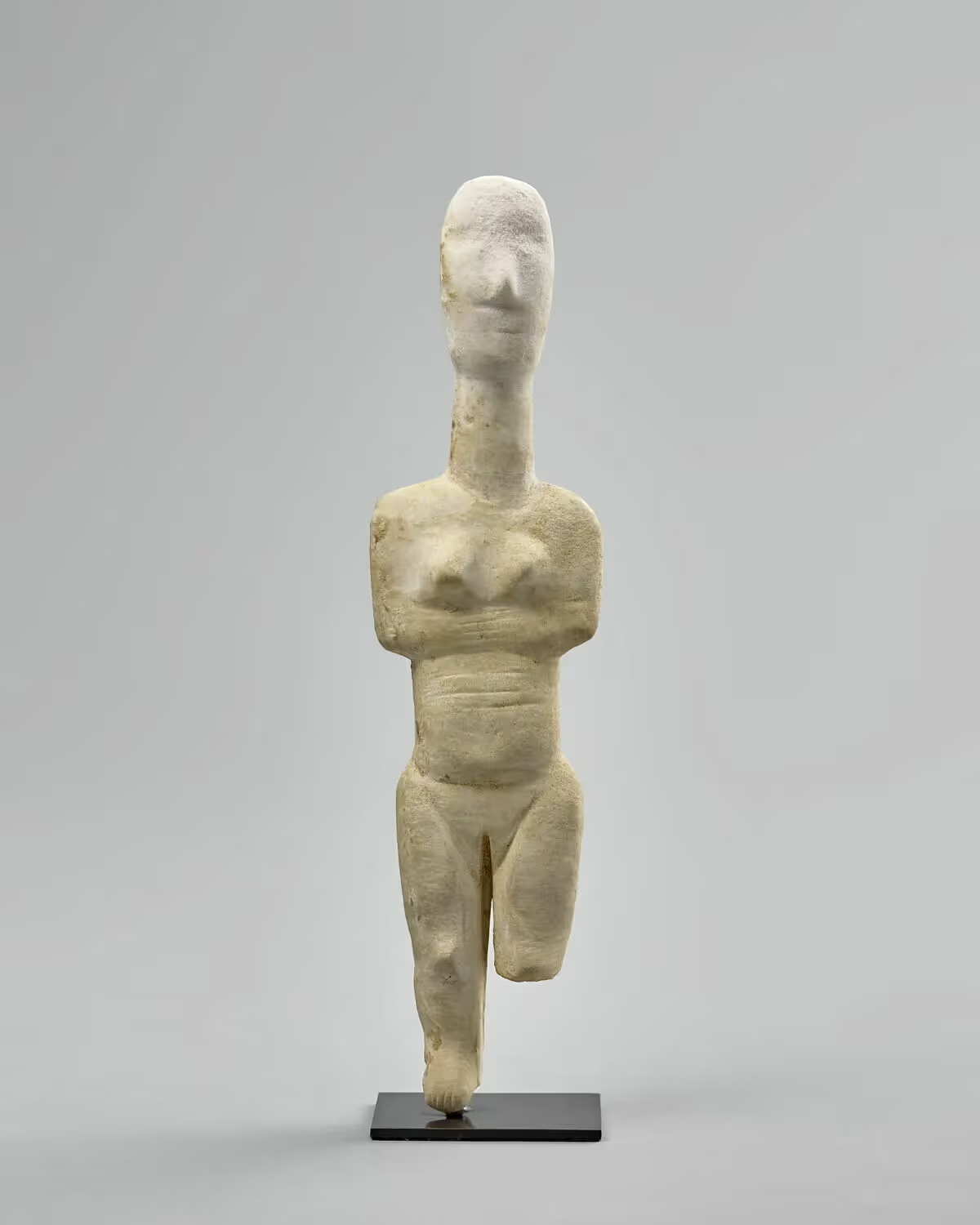

Cycladic idols

These white marble idols have been found in the Cyclades region (Greece) and in Anatolia (present-day Turkey). They date from the Bronze Age, around 3200 to 2000 BC. Idols are often stylized and geometric. They generally feature simplified human forms, with oval heads, flat torsos and very schematic limbs. It's difficult to say with certainty what function these female figurines served, but they seem to have been linked to a cult of fertility and fecundity. Their refined allure partly inspired 20th-century artists such as Picasso, Modigliani and Brancusi.

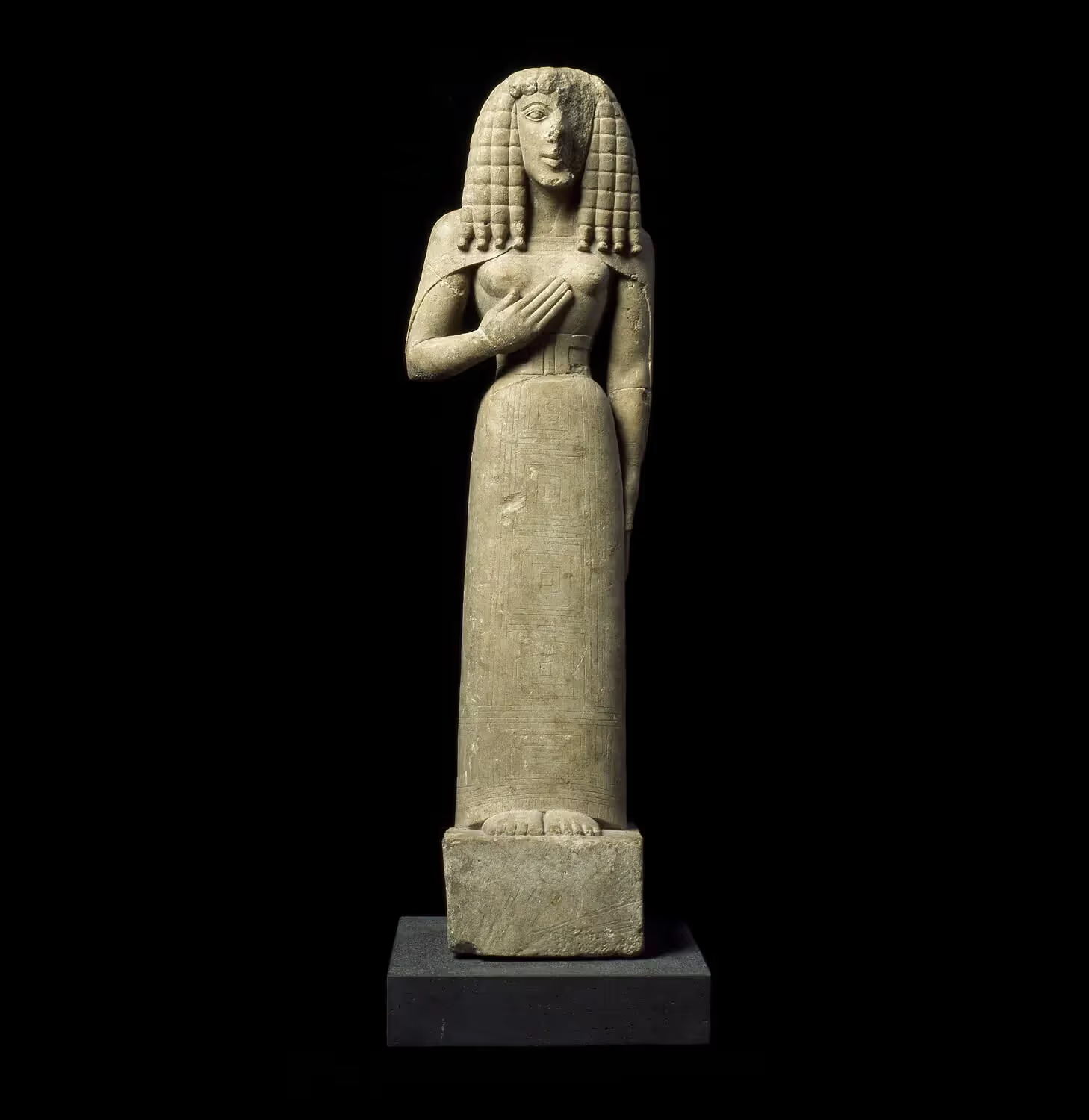

The priestesses

Although each ancient civilization developed distinct cults and pantheons, they all shared the need to appoint intermediaries among mortals to communicate with the deities. This was the role played by priests and worshippers. This function often gave them a degree of political power and considerable influence. Many women in Antiquity held these positions of influence. Charged with praying to and thanking the deities, priestesses helped maintain harmony between the earthly and divine worlds.

This Egyptian sandstone statue, dating from the 15th century B.C., depicts a priestess, an essential figure in ancient Egyptian religion. Priestesses played a crucial role in religious rituals and were often associated with temples dedicated to specific deities. Here, she is shown holding a sistrum, a sacred musical instrument used in religious ceremonies to invoke the presence of the gods and ward off malevolent spirits. These representations illustrate the importance of women in maintaining religious practices and communicating with the divine. In addition to their religious functions, priestesses could also exert political influence, often acting as advisors and figures of power within Egyptian society.

Worshippers were high-ranking priestesses devoted to divinities such as Hathor or Amon, particularly in southern Egypt during the New Kingdom. Their title elevated them to the status of earthly spouse of the supreme god. They were invested with considerable religious and political responsibilities, leading sacred rituals and sometimes exercising political influence that could rival that of the pharaoh.

This statue represents Karomama, a divine worshipper of Amun, in the exercise of her duties. She is depicted walking barefoot and waving sistra, sacred musical instruments used to invoke the presence of the gods and drive away malevolent spirits. The refinement of this sculpture, and its sophisticated gold-inlaid decoration, make it a particularly remarkable example of the art of this period, highlighting both Karomama's sacred role and the skill of Egyptian craftsmen.

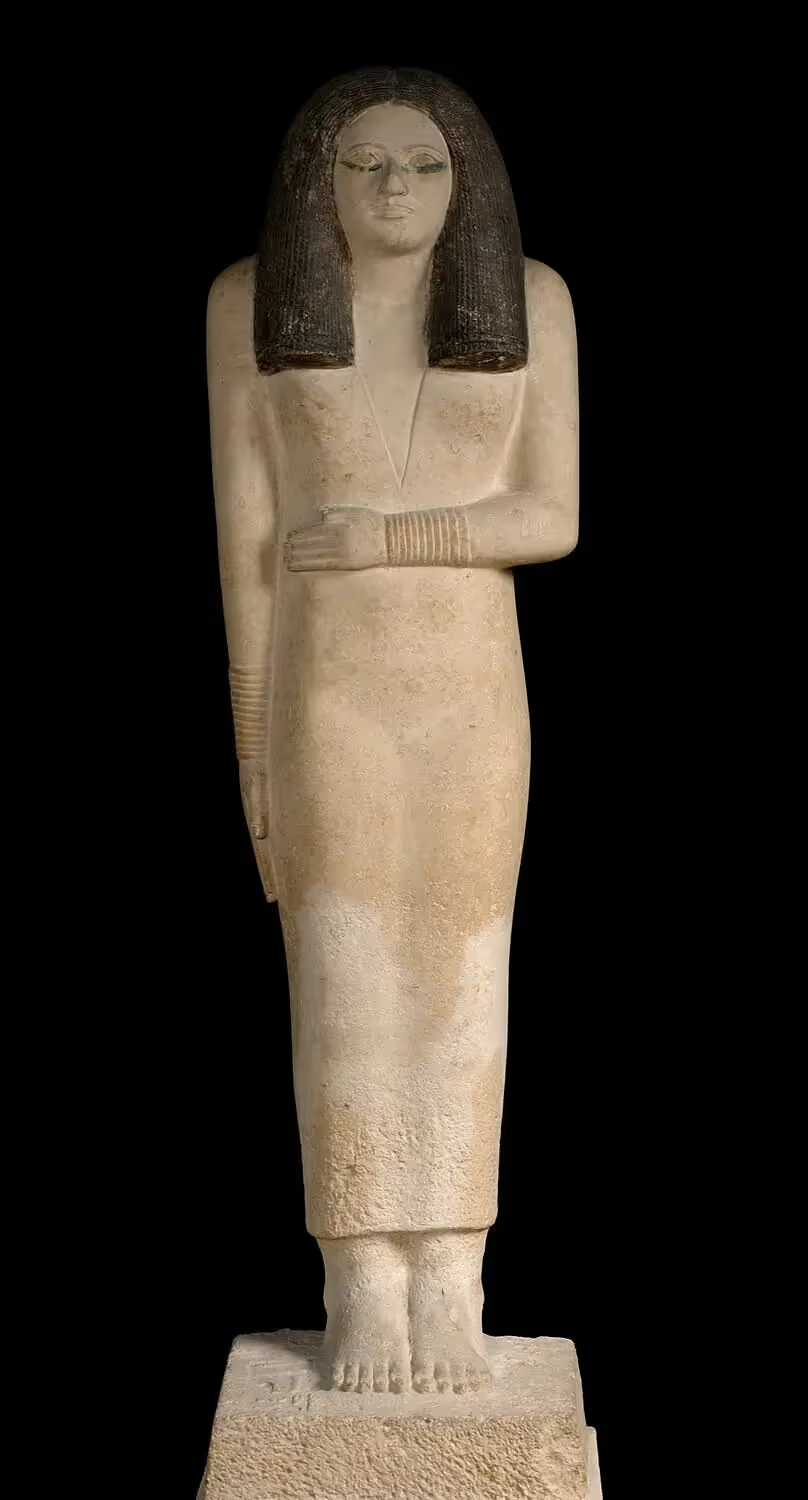

The Lady of Auxerre is a limestone sculpture dating from the late 6th or early 5th century BC. It was discovered in 1907 in the town of Auxerre, Burgundy, France, from which it takes its name. This statue is one of the most remarkable examples of Archaic Greek art found outside Greece. It was originally painted in bright, contrasting colors. Produced around 640/620 BC, it bears witness to the Eastern stylistic influence of contacts between the Greeks and other Mediterranean peoples such as the Egyptians and Assyrians. The absence of distinctive attributes or inscriptions on the statue makes precise identification difficult, but its posture has led some researchers to speculate that it could be a religious figure.

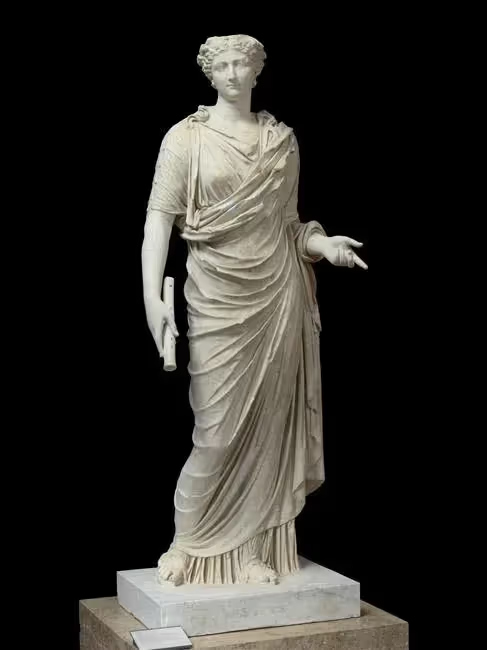

Women of power

To assert their importance and status, some powerful women wear the clothing of priestesses or even goddesses.

Here, Livia, wife of the first Roman emperor, Octavian Augustus (-63/14), is depicted as Ceres, Roman goddess of agriculture and fertility. Renowned for her political wisdom and influence on her husband and son, Emperor Tiberius, she reinforced her status and legitimized her power within the Roman Empire by being represented as a goddess.

This marble statue, dating from the 2nd or 3rd century AD, represents the Roman empress Julia Domna. The Syrian-born Roman empress is depicted here in the guise of a priestess of Isis. This representation underlines the religious syncretism of the time, when cults such as that of Isis, an Egyptian goddess, were present and influential in various Mediterranean areas, as far afield as Rome.

The muses

In Greek mythology, the Muses are the nine daughters of the god Zeus. Each of them is linked to a particular art: epic poetry, lyric poetry, dance, music, eloquence and rhetoric, theater, song and tragedy, history and astronomy... These were all arts that played a central role in worship. Odes, poems and songs were used to honor the gods and goddesses. Today, in common parlance, the people who inspire artists are referred to as "muses".

In these wall paintings found at Pompeii, the muses Terpsichore, Melpomene and Calliope can be recognized by their attributes.

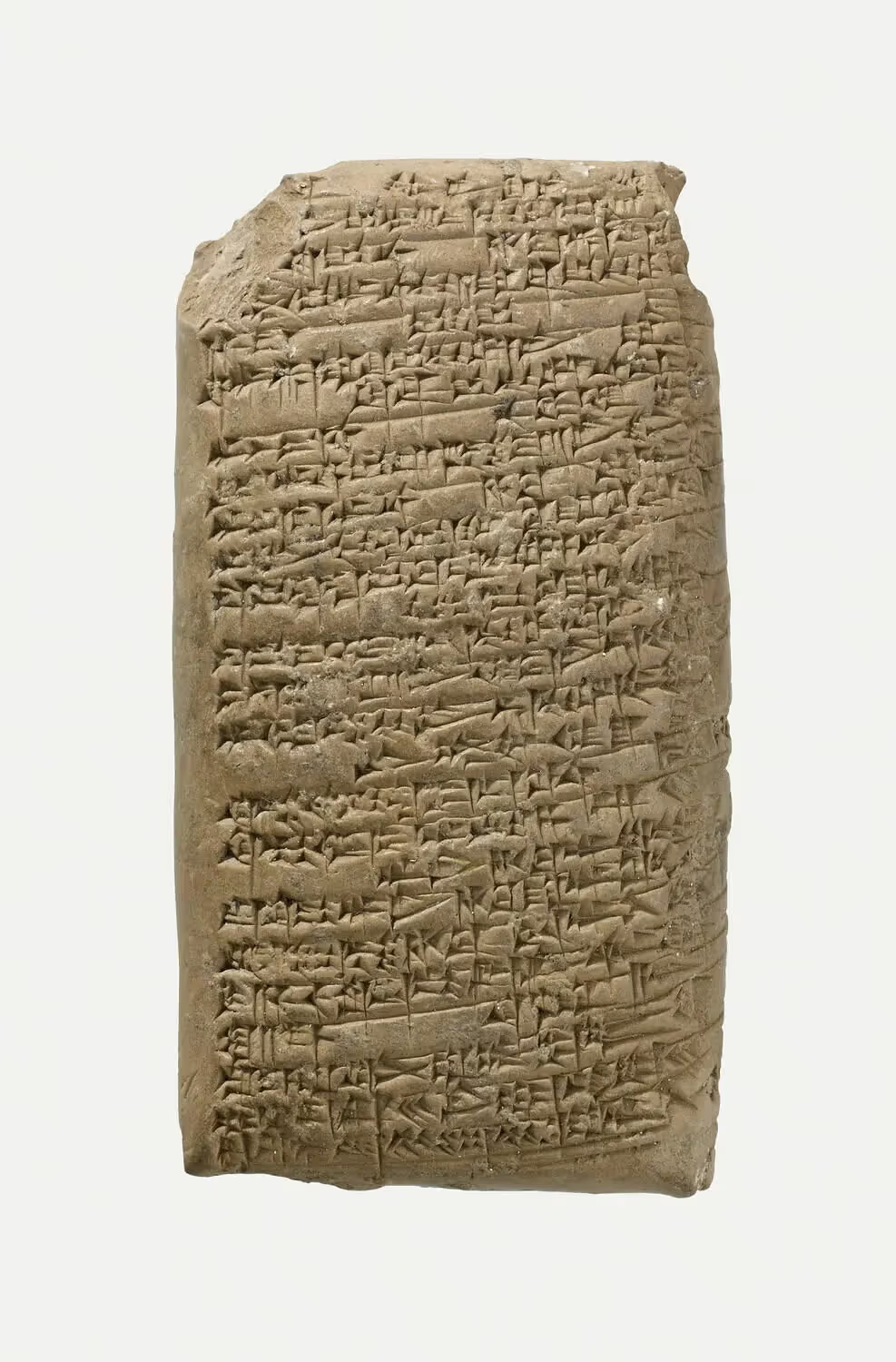

Tablets and papyrus

This tablet transcribes a hymn composed in the 2nd millennium BC, praising the Sumerian goddess Innana. The poem is the work of Enheduanna, high priestess and princess of the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia, considered the first known poetess in history. In this hymn, Enheduanna celebrates the power of the goddess while exploring painful moments in her own life, adding a personal dimension to religious praise.

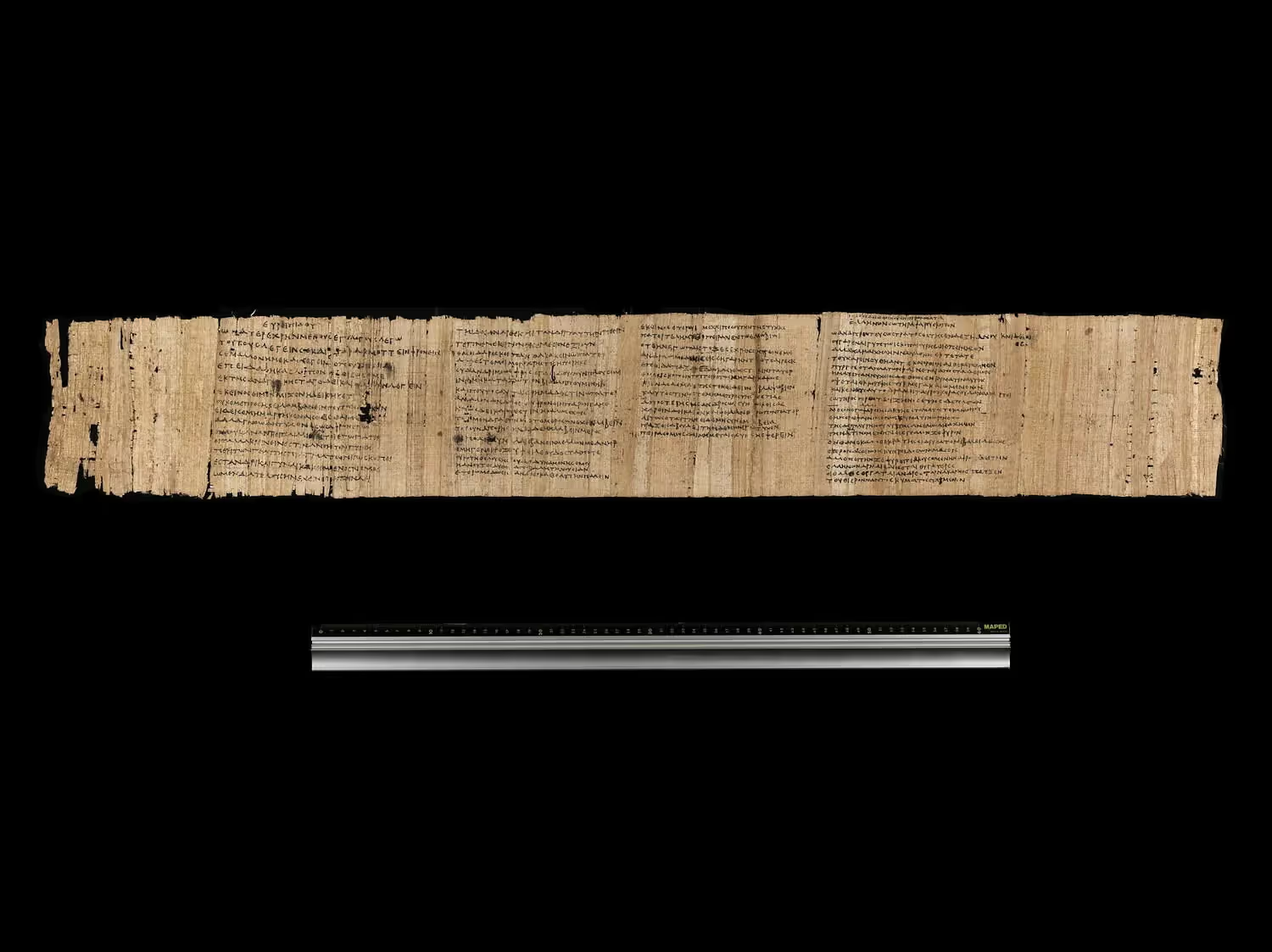

The Papyrus Didot is an ancient manuscript discovered in Egypt that dates back to the time of Ptolemaic Egypt, circa 50-30 BC. It owes its name to its former owner, Ambroise Firmin-Didot, a French printer of the 19ᵉ century. The Papyrus Didot contains a variety of texts written in ancient Greek, some of which are poetic works, such as the Epitaph of Seikilos.

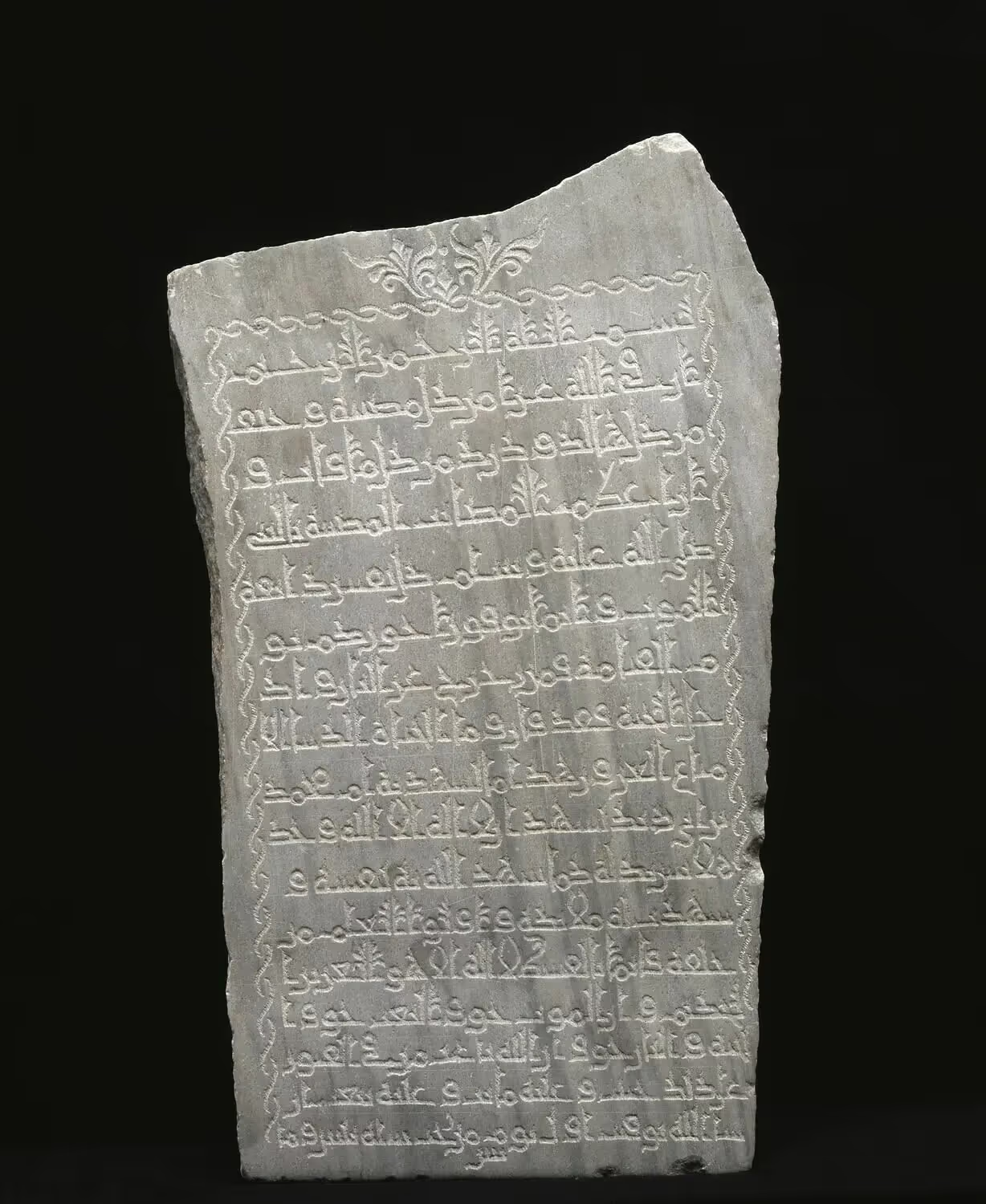

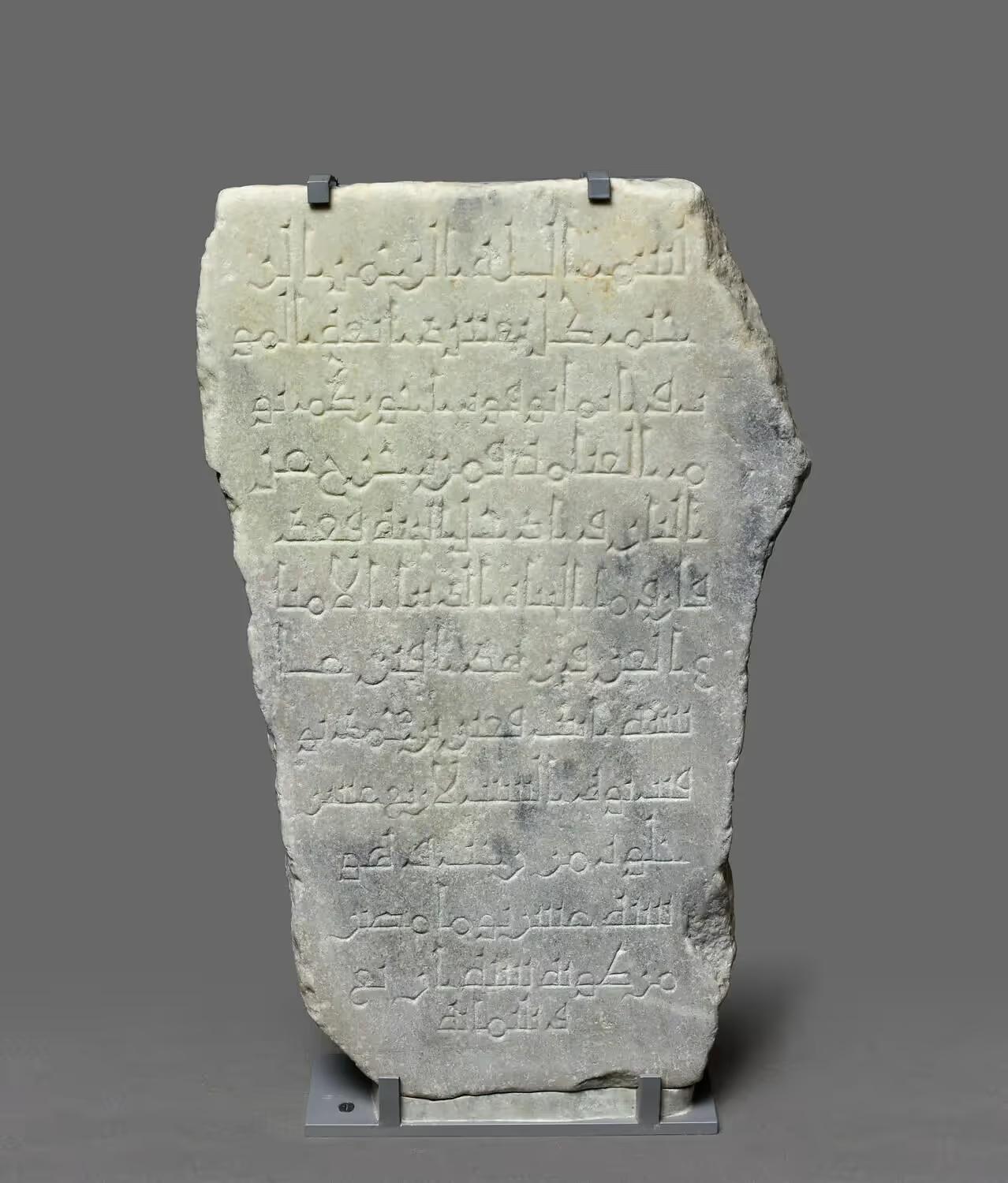

These marble stelae, dating from the 9th to 10th centuries AD, come from Egypt and bear witness to the funerary and commemorative practices of the Islamic era. They bear the names of the deceased and are decorated with geometric and calligraphic motifs.

Cosmetics

In ancient Egypt, cosmetics played an essential role in daily life. Closely linked to religious practices and spiritual protection, they were also associated with wealth, health and beauty. The Egyptians used a variety of natural substances to create their cosmetics, including kohl, the most emblematic eyeshadow, made from minerals such as galena and malachite. Eyeshadow pots and palettes were precious, richly decorated objects, often made of stone, ivory or wood, used to store and mix cosmetics. Adorned with religious motifs or symbols of protection, these objects bear witness to the importance attached to beauty and ritual in ancient Egyptian civilization. The quality and sophistication of cosmetics and their containers reflected the social status and wealth of their owners.

The Treasure of Boscoreale is a remarkable collection of objects discovered in a Roman villa near Boscoreale, an ancient town near Pompeii in Italy. The villa, buried under volcanic ash when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD, was rediscovered in the 19ᵉ century. The treasure comprises an impressive collection of silver objects, including crockery, jewelry, tableware and decorations. It thus offers a valuable insight into the daily life and luxury of the Roman aristocracy of the period. Toilet mirrors in particular were distinguished by their precious appearance. One of these mirrors depicts the nymph Leda and Jupiter metamorphosed into a swan.

The Mediterranean landscape

Female divinities

Female divinities play a significant role in the mythologies and religions of the Mediterranean basin. Possessing powers superior to those of humans, they embody primordial aspects of nature and existence. Each goddess offers protection in a particular area. By dedicating prayers and offerings to them, the faithful seek to win their favor.

This Phoenician gold mask, dating from the 1st millennium BC, may be a representation of the goddess Hathor. It was found in the city of Byblos (now Jbeil in Lebanon), where a sanctuary honored her. Hathor, a figure of Egyptian mythology, was the goddess of joy, beauty and love.

The Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar is depicted on this stele from the 8th century BC. This goddess embodies love and femininity, but also warrior strength. Here, she stands on a lion, her animal-emblem, with weapons protruding from her shoulders. Ishtar enjoyed an exceptionally long cult, lasting almost 10 centuries throughout the ancient Near East.

This crater (a vase used to mix wine in ancient Greece) dates from the 4th century B.C. and depicts the abduction of Europa. This myth recounts how Zeus seduced and abducted Europa, a Phoenician princess, by transforming himself into a white bull.

Isis is an Egyptian goddess associated with fertility and love. She is often depicted in a protective attitude, accompanying the deceased. Here, her gesture recalls the role of the mourners who, during funeral ceremonies, had to express both the grief of the deceased's family and move the deities.

This stele represents Tanit, a Punic goddess associated with fertility. Punic civilization, mainly located around the city of Carthage (now Tunis), gradually disappeared following numerous conflicts with Greek cities.

This Roman statue depicts a female figure clad in a dress whose drapery imitates the effect of wet, heavy, sticky fabric, accentuating the sensuality of the body. Over time, it has been added to several times. This statue could represent a goddess, such as Venus, or a mythological character, although its precise identity remains uncertain.

Athena, or Minerva to the Romans, is the goddess of wisdom and military strategy. This statue depicts her with her attributes: helmet, gorgoneion (sculpted Medusa head)... This Roman statue from the 1st century AD is also known as the Pallas of Velletri. It is a Roman copy of an original Greek statue. At the end of the 18th century, it was restored by an Italian sculptor who chose to complete its missing parts. He added the goddess's right arm and helmet.

This sculpture is a Roman copy of a bronze work attributed to the famous Greek sculptor Praxiteles. It depicts Apollo ready to kill a lizard.

This sculpture depicts Diana, the goddess of nature and the hunt, in a dynamic pose, running alongside a young stag. Since the 16th century, it has been an integral part of French royal collections, and has been exhibited in various châteaux of French kings. This Roman copy is often associated with the Apollo of Belvedere, another sculpture attributed to the same Greek artist, Leochares. This connection between the two works highlights the influence of Greek mythology on Roman art, and underlines the importance of depicting divinities in ancient culture.

Women, love and couples

The portrayal of women as couples offers valuable insight into the norms and values surrounding conjugal relationships in a given era.

In this painting, Italian artist Mantegna depicts Mount Parnassus, near Delphi. In the center, the lovers Mars and Venus, god of war and goddess of love, are featured prominently. They are surrounded by Apollo playing the lyre, Mercury and Pegasus, and the nine Muses dancing in the foreground. Vulcan, Venus' husband, watches the lovers from his forge. Commissioned by Isabella d'Este for her studiolo, Mantegna's painting was inspired by the patron and her husband to create the central couple.

In ancient Egypt, the role of the woman in the domestic household was above all that of mistress of the house: she managed the household administration, the servants.... She had to be a devoted wife. Here's the scribal inspector Raherka and his wife Meresankh, a couple immortalized in 2500 BC. The man is in motion, with darker skin: he embodies action and work outside the home. Meresankh is slightly set back, in a static, more passive position. Meresânkh adopts a protective and supportive stance towards her husband Raherka, embracing him with her right arm.

The statues of Sepa and Nesa, carved around 2700 BC, are among the earliest life-size representations of notables in ancient Egypt. These limestone statues were used to render eternal the presence of the deceased in tombs. The couple is depicted in an idealized way, reflecting their social status and exemplary lives. The male figure is in motion, while the female is static. Nesa embodies an ideal youthful figure, dressed in a tight-fitting dress that marks her femininity.

But around the Mediterranean, situations can be very different for women from one culture and era to another. The Etruscan civilization, for example, which settled in north-western Italy before the arrival of the Romans, guaranteed women considerable freedom and rights for their time. This sarcophagus, known as the Sarcophagus of the Spouses, dates from the 6th century BC, and shows us that women took part in banquets alongside their husbands. These were strategic moments for alliances and meetings between families. Here, the man is shown behind his wife, in an embrace that places them both on an equal footing.

The family

The figure of mother and child is a frequent representation of ancient Mediterranean women.

This bas-relief from the Hittite period, discovered in Turkey, depicts a scene of complicity between a mother and child. The child is already in his teens, as his hairstyle indicates. This mother and her adolescent child seem to be very close. The mother stands in the lower part of the stele, seated on a stool, and affectionately wraps her arms around the young man.

This fragment of a marble funerary stele was part of the architecture of a Christian church in Thessaly. It dates back to the 5th century BC. It depicts two women facing each other, dressed in a Greek woollen tunic, the peplos. They are holding poppy or pomegranate flowers. Their identity is unknown: are they a mother and daughter? Two goddesses?

This Athenian marble stele depicts the deceased surrounded by her mother, children and maids.

This funeral banquet scene, produced around 225 AD, shows a man half-reclining on a bench, holding a cup, while at his feet is a woman, his mother, depicted on a smaller scale.

Portraits and emotions

Works of art from the ancient world show us faces and lives, from one side of the Mediterranean to the other. The expression of emotions through art is an ancient tradition, as evidenced by the image of this Egyptian mourner, who raises her hand to her head in mourning in the 2nd millennium BC. During Egyptian funeral ceremonies, the role of mourners was not only to express the grief of the deceased's family, but also to move the deities.

This portrait, painted on wood, represents a deceased woman. Executed during the young woman's lifetime, around the 2nd century AD, it was found above her mummy in the Fayoum region of Egypt, replacing the funerary mask. It is one of the oldest painted portraits of antiquity. These paintings show how cultures intermingle and influence each other as they interact. Despite Roman domination, Egyptian civilization maintained its funerary rituals of mummification, while adopting Roman clothing and naturalistic artistic representation inspired by Greek art.

The "Battle of San Romano" is a series of three paintings created by Paolo Uccello in the early 15th century. Each of the paintings depicts a different episode in the Battle of San Romano, which took place in 1432 between Florence and Siena during the wars between the Italian city-states. The paintings are remarkable for their innovative use of perspective and their detailed depiction of battles and horses. They are also remarkable for their complex composition and use of light to accompany movement. This series of paintings is an early example of the Italian Renaissance style.

La Belle Ferronnière, a portrait attributed to Leonardo da Vinci around 1490, depicts an elegantly dressed woman facing three-quarters to the left. Her dress, jewelry and hairstyle are typical of the fashion of Milan's upper middle class in the late 15th century. The identity of the woman in the painting has given rise to many theories, but remains uncertain. Some have suggested that she could be Lucrezia Crivelli or Cecilia Gallerani, two women associated with the Sforza court in Milan.

Attributed to Christophe Cochet, this marble sculpture depicts a woman holding a dagger. Since its creation in the 17ᵉ century, its identity has evolved over time: it has been successively identified as Lucretia, Cleopatra or Dido All figures of ancient women who voluntarily gave themselves death.

"The Abduction of the Sabine Women" is one of French painter Nicolas Poussin's most famous works, painted around 1637-1638. It depicts a legendary episode in the history of Rome, in which the first Romans, led by Romulus, captured the women of neighboring peoples and forced them to become their wives. Surprise, fear, anger, resignation... the painter explores a variety of emotions in this composition, one of the most famous in French painting. This myth also inspired many works from the Renaissance to the 18th century, giving artists the opportunity to depict female characters in struggle and to portray expressions of fear and panic.

This work by Swiss sculptor James Pradier represents the poetess Sappho. This major literary figure of Greek antiquity has inspired many artists throughout the ages. Born in the late 7th century B.C. on the island of Lesbos, Sappho is said to have founded a school of poetry for women. Among her most famous poems is a poignant hymn to Aphrodite, in which she begs to be freed from the love she feels for a young girl.

.webp)

.webp)

%20(2).webp)

.webp)

.avif)